I mentioned this idea almost offhandedly in a training recently and it was profoundly exciting to the people in the training— so I’m making it into its own post!

Here’s the idea in brief: ask kids to plan ahead, and write their idea down. And then reference your written note about it at a later time, in front of them. Write it by hand if you can, but modeling writing it in your phone or doing a voice memo is great too!

Here’s what that looks like in practice for me. I have a few OT kids in particular with whom I do this. These kids hate writing and do not see ways in which writing is meaningful. Writing is something adults force them to do about pointless topics that they do not have any emotional connection to. It hurts their hand, it’s meaningless, and it’s a demand handed down from “on high”.

Relatedly, as part of the same pattern, these kids are used to being excluded from decision-making in their own care. Their opinions are not valued as partners in their own care. They might be given token choices like “do you want to do your writing or your math first today” but not choices that feel like big, meaningful choices.

Also relatedly, most of these kids either struggle with some aspect of executive functioning— skills like organization, planning, beginning a project, conceptualizing how many steps the project will take, switching from one task to another, time management, etc— and having some kind of executive functioning support, or just practice, is helpful for them.

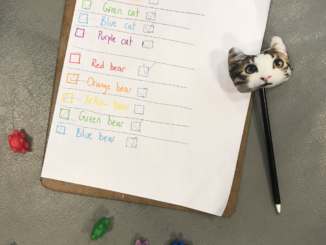

So, given all that, here’s what I do. I have a journal and it says on the inside, i.e., “Harper’s Journal” (none of my kids is actually named that). At this point Harper is looking at me skeptically like “are they about to try to make me write in there”, nope. I get out one of my wacky pens and I’m like “ok Harper — the next time I see you for OT will be next Tuesday, seven days away. What game do you want me to have up on my tablet when you get to my room?”

Or, “what song do you want me to have playing,” or, “where do you want me to put the dinosaurs in the room,” or, “you mentioned earlier that I should refill the blue paint, anything else?” or…whatever. Whatever is authentic to that child. They might’ve expressed a wish sometime during the session and if so, now I’m modeling writing that down (or I did it at the time they said it). Or we might have a more detailed plan, like, “we were going to invent that board game together so you said we need cardboard and a black sharpie that actually works, anything else I should look for?”

Some kids have tons of ideas. Some kids have no ideas whatsoever. I scaffold for some of them—like the “what game should be up on my iPad” question. That’s hardly an irreversible decision if they change their mind.

Then the next session I do the thing they said before they get there, and when they get there, open the book first thing. Or it’s lying open on the floor next to the setup. “Aha, I remembered you said you wanted the cat game! I have it set up for you. Unless you’ve changed your mind?”

“Unless you’ve changed your mind” = “it’s ok, you’re still the care partner here. You can change. You have all the power you need, no need to fight for it. We’re a team, it’s ok to change your mind!”

If they change their mind, great! Maybe they needed an extra boost of feeling like they can believe and trust you. Or maybe they genuinely had a different idea. Or maybe they’re flexing their “planning ahead, vs, remembering later” muscles. It takes skill to look forward into the future and backward into the past; to remember that thing you said before.

If they don’t change their mind, great! A successful carried out plan.

Here’s one way I think this could work in a classroom of young kids: if you have “classroom helpers” (line leader, person who hands out papers, door holder, etc) could one of your classroom helpers be the DJ? They’re in charge of picking out the instrumental music or white noise (from a selection, not from all music in the world) that plays during your quiet independent work time for the week— and maybe also something fun like one fun song to play at the start of the day that’s like a kids bop pop song or a YouTube kid singer song or whatever. Pull them aside for 2 minutes at the end of the day, have them choose for tomorrow, write down their choice, carry out the plan.

(You get added points, and my love and affection, if you take the chance at the start of this idea to explain to kids that people’s senses of hearing are all different, so some people notice very quiet sounds and some people don’t. And some brains not only notice quiet sounds but they start being on red alert for quiet sounds because they think, “what if the sound is important or dangerous?”, even though in a school, we know that the teachers can tell us if something is important or dangerous. And how in a school, then sometimes listening to music or noise can help the people whose brains do red alerts for quiet sounds, because their brains don’t have to do all that work noticing all the sounds. The brains can just relax a little more and think about their school work.)

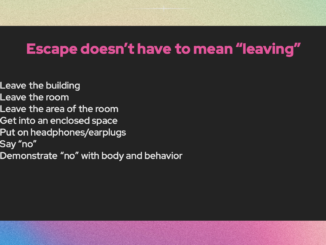

Here’s one way I think this could work in a classroom of older kids: take 5-10 minutes at the end of the day, or maybe once a week, and think together about how the day went. Was there a time that anybody struggled to focus? Share an example yourself (as the teacher) if you can. Now think about tomorrow. Is there any sensory thing that could be a support to avoid that same situation if it happens? Write some of them down on the board, or in a journal, and reference it as a reminder the next day.

For example, you as the teacher: “I noticed that I got overwhelmed and shouted when you guys’ voices started getting loud during independent math work time. I didn’t plan to shout, but it started to make me feel anxious and that’s how I reacted. Next time I’ll try to remember to flash the lights to get you guys’ attention without my voice!” (Write “flash the lights” on the board)

Or, “I noticed that during social studies we were all dragging along. Me too, I could feel it too. I wonder if tomorrow having some upbeat music playing in the background might help us feel less sleepy, since it *is* right after lunch and that makes me feel tired.” (Write “upbeat music during social studies” on the board)

Here’s two ways I could see this work at home: your kid has an idea right before bed and it is an involved idea, not possible to do right before bed. You agree that it’s a great idea, write it down for them, and then support them through however they feel about not getting to do the idea. (You were going to have to do that anyway. All we’re adding is that you physically wrote down the idea!) the next day, before they ask about it and regardless of whether they remember, you ask them at a good time for you, “remember the idea you had? Do you want to do that? I can get the supplies right now!”

Another way you could do this: maybe your kid wishes to have access to screens instantly in the morning but you feel that’s not right for your family for whatever reason. Maybe a compromise you could come to is that you ask them the night before, “what ambient video should I have on tv when you wake up?” I’ve written about ambient videos in our family before— fireplace crackling, thunderstorm happening, fish going by, cute baby animals, etc. Then in the morning you have it on for them before they wake up.

These are a handful of suggestions that are not meant to be exhaustive, nor is new change ever usually a stellar success on its first try. There are a million other ways you can begin inviting your child in OT, in school, or at home to begin participating in thinking forward to the future, making a plan about something that matters to them, and then you modeling a way to use an executive functioning tool to remember it and carry it out on their behalf, because they are important to you and their ideas are important, important enough to write down!