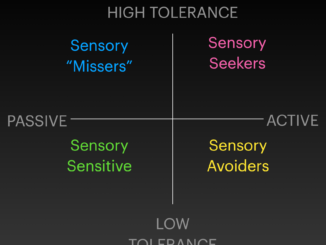

I have had lots of questions from people about “sensory mismatch” lately. Sensory mismatch is my phrase for it when two (or more) people in the same environment (like home, a classroom, etc) have different sensory processing styles, AND those different processing styles are causing a clash of some kind.

I recently gave a whole lecture on this topic, so for the next 5 days I will be posting 5 posts about sensory mismatch.

If you don’t know anything at all about sensory processing, it might be helpful to read some materials on that first. You can search this website by the tag sensory processing, or, this post is a good place to start.

Really when it comes to solving sensory mismatch it can be easy to solve two factors, or at least to think of a hypothetical solution that could work for two factors. What if person A hates loud noises and person B stims by making loud noises? Well, give person A headphones. Those types of situations that have only two opposing senses involved can be generally easy to imagine a solution for. The tricky part usually comes when you start mixing in all the other senses. What if person A hates having tactile sensation on their ears? Well, maybe make person B go outside. What if person B is overwhelmed by the visual sensation of bright light, what do they do when it’s sunny? Well, wear a hat. What if person B hates having something on their head…? Etc. It’s almost like you have to keep running through the next set of flags to solve new problems over and over and over, or like whack-a-mole as you try to keep fighting each one as they pop up.

So if you’re trying to expand your toolbox to deal with more real-world scenarios (in which there aren’t only 2 factors), here’s my first “tool” for you to have.

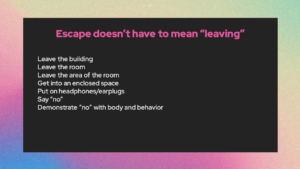

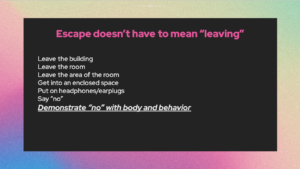

I think that the number one thing is that all parties involved should always have a safe option for escape. If that doesn’t exist, then that needs to be the priority. In the classroom, at home, at the store, whatever. Adults included. Figuring out what the safe version of that for the particular situation is, may take some doing. That’s because all of this may take some doing.

Remember that escape doesn’t have to be physical escape. It might mean leaving the room to go to the next room, it might mean leaving the room to go to the hallway, it might mean staying within the room but getting into an enclosed space, it might mean staying within the room but putting on headphones or earplugs. Sometimes phrasing it as “escape from the ____ input” might help you pinpoint exactly what kind of an escape you or the child need and that might help you figure out how to implement it in a safe way.

In an ideal situation, you’d want to have multiple options, but the priority here is just starting with one. You can even write it down if that helps you.

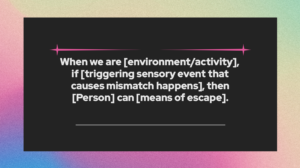

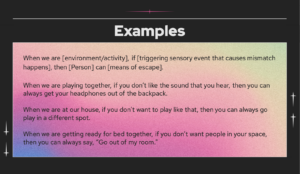

When we are [environment/activity], if [triggering sensory event that causes mismatch happens], then [Person] can [means of escape].

It sounds convoluted with all the brackets in it. Here’s what this sounds like in my house. I say a variant of this at least weekly if not more often: “You can always put on headphones if you’re bothered by the sound somebody is making.” “You are allowed to leave the room if you don’t want to play like that.” “You can always go play somewhere else if you want to be left alone.”

I try to phrase my sentences so that nobody is getting “blamed”. I don’t say, “You can put on headphones if Summer is annoying you,” because now I’ve framed Summer as the “bad guy” and Apollo as the “victim”.

I try to model it with my own body too. Summer often notices that I’m wearing earplugs and I say something casual like “Yeah, I always put on earplugs when the house feels too loud to my ears.”

Remember that it’s not always auditory. Imagine how you would plan with a child how they will escape visual input that’s overwhelming? How about tactile, touch, input that’s overwhelming? How can a child escape taste input that’s overwhelming? What about movement input that’s overwhelming? This sometimes requires critically reexamining your own personal rules about what is allowed for kids to self-advocate. It might be categorized in your mind as being “rude” and therefore unacceptable, so you won’t let your child close their eyes if their visual is overwhelming, or say they don’t want to eat something they don’t want to eat, or take their food elsewhere and eat it if the smell of someone else’s food is bothering them, or avoid giving hugs or kisses. I would say that all of those choices are self-advocacy and are really important.

In the next post, I will talk about the second tool that I think can help with sensory mismatch.

***