This is going to be very long. And this was the hardest post to write this month. I sat down to write it three or four times before I was actually able to make myself do so. I’m going to do my absolute best to write it with grace and empathy; I hope you will do your absolute best to read it the same way.

If you are Autistic, this may be a very triggering post (about Autistic trauma), and it might be wise to skip.

If you are the parent of an autistic child, please, please set aside the time to read it.

I don’t remember when I first learned the word “autism” or who it was in relationship to, specifically. But I do know that a very early portion of my learning about it had to do with kids who were adopted internationally. That’s a big part of my journey towards OT, and towards working with kids with disabilities, so it also informed a big part of my early knowledge about autism.

Here’s something that I understood very early on, but didn’t have the language to put into words, though. Some kids come home from international adoption, they have been left in a crib all their life. They may have even been restrained to the bed. Or they might not have had “as” severe of circumstances, but they had no safe person with whom to attach, to learn to play. Their only stimulation might have been their own hands, or a single toy, or a handful of toys. They might have learned to flap their hands beside their face, to rock back and forth, to bang their head, to self-injure.

A doctor might look at those symptoms and diagnose them with autism.

Are they wrong? I don’t know. Would that person have been Autistic in completely different circumstances, if they had been raised by their biological parents, if their life trajectory had been something else entirely? Maybe. We know autism is genetically related; we know that it’s a neurological wiring. But we also know that some trauma symptoms are similar or identical to some autistic traits.

I use that as an egregious example (although it is not a rare occurrence, by any stretch of the imagination) in order to illustrate this point: There is a gap — in the research base, in the diagnostic criteria — between understanding which of those “similar or identical” behaviors are common in Autistic people because of their trauma, and which of those behaviors are common because of their autism.

That’s because Autistic people have been historically, and are still presently, traumatized. By having to live in a world that isn’t built for them. By continual exposure to overwhelming sensory experiences that hurt their brain and body. By their treatment at the hands of neurotypical people. Sometimes well-meaning neurotypical people. Sometimes not.

The gold standard for autism treatment in America, the one that almost all insurances will pay for and sometimes the *only* one they’ll pay for, is ABA therapy: applied behavior analysis. Nearly half of all autistic children exposed to ABA therapy will meet the criteria for developing PTSD, four weeks after beginning ABA.

But if the kid keeps getting ABA treatment, the parents’ satisfaction scores trend upward. Even as the PTSD worsens.

Remember when I defined “masking” as having to suppress autistic traits? Having to hide them? That for decades, our primary “cure” for autism has been, well, let’s teach autistic kids how not to look autistic? That’s what ABA is. And that’s why it targets parents’ satisfaction.

ABA was invented by a clinician who used shock therapy and other aversive therapies for a number of reasons. He tried to use it to make gay people straight. And he used it on autistic kids to make them try to seem not-autistic. He famously spoke of autistic people as being the “raw materials” and his job as being “to build a person”.

Most ABA companies acknowledge all of this these days, because they claim to have moved away from their past. But as recently as 2021, they’re having a conference where, among other topics, there’s a panel about protesting an FDA ban on shock devices for kids with autism. (Yes. They would like the FDA to overturn their ban so they can keep using shock devices in the cases in which they currently do.)

Not all behaviorism is so egregious. In fact, the overwhelming majority of it isn’t. But when a treatment has its roots in such trauma-inducing tactics, it’s worth carefully scrutinizing, and careful scrutiny comes away with studies like the one linked above. The kids who are coming away with PTSD aren’t kids being electroshocked. They’re just kids sitting through “normal” ABA treatment sessions, which are behavioristic and tend to follow a predictable pattern: build a rapport with the child, find something they’re attached to, then take it away until they do what you want, and train them to do what you want. “What you want” often being code for “what makes them look neurotypical”.

Why would anybody seek ABA? It would be really easy to point a finger at the parents and say that parents just are so obsessed with having a kid who isn’t autistic that they’re willing to do anything to them. In my experience, that’s not the case. Parents love their kids and want what’s best for them. And ABA practitioners are trained to use scare tactics to overcome parents’ objections to the treatment.

In my experience, parents are scared and desperate and don’t know better. They’re not looking to Autistic adults to hear what they’re saying. The doctor who diagnosed their kid didn’t even tell them there were Autistic adults out there speaking up. If they found out any kind of support group or resource group, it’s usually a group of non-autistic parents of autistic kids sitting around and commiserating about how hard it is to have autistic kids. And they’re clinging to what society tells them their child needs to look like and act like. They need to be toilet trained by (some arbitrary age). They need to behave socially in (some arbitrary way). They need to make eye contact (some arbitrary amount) and they need to stim only under (some arbitrary circumstances).

I have heard too many Autistic people’s stories to count, of how they learned to mask because they were forced to. They didn’t become less Autistic. Instead of flapping their hands they might have learned to pick at their skin or chew the insides of their mouths or just suppress all of it until it explodes in a self-injurious meltdown.

Here’s the thing. By no means do I claim to speak for every single autistic individual in the world. But as best as I can understand it, it is traumatizing to live in an autistic body. Sensory overload, social ostracization, unhelpful “treatments”, it all reinforces that the person is not safe and that being themselves is wrong and bad.

So along comes ABA — and other treatments, by no means is ABA the only offender, it’s just the biggest one. Behaviorism is also woven throughout schools and “positive behavior intervention programs” and therapies, including OT. And these practitioners promise they can make the child look better on the outside. And depending on how much they’re willing (or not willing) to listen to the communication from the child, in whatever form the child chooses to communicate it, even if it’s not a neurotypical method of communication…they may or may not come away from that thinking they’ve succeeded.

All that means is that instead of looking outward for help with this trauma, the child has internalized it. It has become a part of them.

I have heard a handful of people tell me, “But we had to do ABA because it stopped our child from a self-injurious behavior.” Maybe they used to bang their head or they used to hit themselves and ABA training stopped them. (Or maybe, and commonly, the child began to do some of those types of self-injurious behaviors shortly after starting ABA…and then the ABA therapist can point out that they’ve made progress on X metric but now, look, now see what they’re doing, now we need to address this too…)

And, like I’ve mentioned before, it’s often the only therapy that insurance will pay for in the US — and that’s no small factor. It can be up to 40 hours a week of therapy. (Don’t get me started on the fact that toddlers and small children should not have a full-time job, nor should therapies take as much time as one to be “successful”.) There’s even more complicated factors when you consider that that might be an impoverished or under-resourced parent’s best access to care during the day for a child younger than school age.

I liken it to this hypothetical. Imagine if someone showed you a sealed room, with a window overlooking it. Through the window you can see a young toddler and a hot oven. And this person tells you, “We have to keep the baby away from the oven because he’ll hurt himself. So every time he gets close, we can push this button and it’ll shock him.”

Sure, it hurts the toddler, but it’s better than burning himself on an oven, right? So what if maybe the toddler eventually stops doing anything at all, stops exploring anywhere at all, curls up in the corner and is afraid to come out. At least we stopped him from burning himself?

And I’d like to take a step back and say, why is the toddler in this room to begin with?

Why are autistic people trapped inside a system that is so traumatizing that the options may be to hurt themselves or for other people to hurt them?

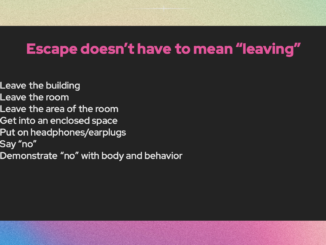

I know it’s far from a scholarly source, but the first article I ever read about this was on tumblr, so I’m going to share that specific post. It meant so much to me that I immediately saved it as a bookmark on my phone and I’ve had it ever since. In it, an adult with autism is saying, “I wish there was a kind of ABA therapy that’s different from what ABA therapy is.” They go on to describe how this imaginary therapy would, rather than trying to have made them look normal, have helped them adapt to the things in the world that were hurting them (like sensory overload), and helped them learn to love the things about themselves that weren’t harmful but just seemed different from other people. Please read it. All my other links in this post were citing sources, but this one is simply sharing an Autistic person’s words.

The therapy that author is describing isn’t ABA. It doesn’t exist in ABA. It is quintessentially and at its core not what Applied Behavior Analysis is about. But it can be OT. And it can be parenting. And it can be speech and PT and teaching and mental health and a thousand other little venues. If we decide as a collective that we’re going to make the world inclusive instead of making it so exclusive that we hurt people, that we trap people in rooms where they must hurt themselves.

If we decide that autism shouldn’t also immediately trigger a secondary diagnosis of trauma.