There was once an occupational therapist working at a school. The occupational therapist had a young teenage boy on their caseload. They were supposed to see the teenage boy to work on handwriting goals. The therapist could work with him for thirty minutes every week.

The therapist spent a lot of time thinking of creative ways to coax the boy into working on handwriting, or even fine motor games or activities. They would show up with things printed off from therapy websites, sit down at the table across from the boy, and try to convince him to practice his handwriting. There were games like, “roll a dice to see what prompt you get and then write a sentence about it,” or like, “write something that starts with S for these 10 categories”.

The boy was pleasant and kind and polite and wholly uninterested. He would do the absolute bare minimum required with the shortest words he possibly could. He wrote as slowly as possible so that writing one sentence might fill the whole thirty minutes. He chatted about his favorite things to fill the rest of the time. The therapist tried sometimes to get him to write down his ideas and he would smile and nod and keep chattering away at them, writing as little as possible.

Writing was not meaningful to the boy. Writing was something that adults forced him to do, sometimes. Because he had a brain that wanted to please the adults, and because he had good adults who cared about him, he would sometimes do his best. But all the worlds that lived inside his head couldn’t come out on the paper through his hands. He had lived long enough to know that. He was tired of trying.

***

There was once an occupational therapist working at a school. The occupational therapist had a young teenage boy on their caseload. They were supposed to see the teenage boy to work on handwriting goals. The therapist could work with him for thirty minutes every week.

The therapist showed up to the first meeting with the boy with no agenda in mind. No plan to get anything done other than to meet him and find out what he liked. The boy mentioned he liked checkers. The therapist couldn’t immediately think of a way that checkers would have to do with writing. But the therapist had seen magic happen when they followed children’s lead. The therapist showed up the following week with a big sheet of paper, markers, and plastic multicolored frogs. The therapist began drawing a checkerboard, apologizing for not already owning one but happy to make one to play checkers. The therapist and the boy set up frogs to be the checkers and made about 3 moves of an actual checkers game.

The boy was pleasant and kind and polite and wholly invested. He began to share ideas about his favorite things, imaginary worlds that lived inside his head. He started telling a story and the checkerboard was quickly forgotten. Over the weeks, the therapist brought more and more paper, scissors, hole punches, staplers, tape, glue sticks, fidgets, stickers, blocks, toys, a tablet, a typing keyboard. The therapist and the boy made up an ongoing collaborative imaginary story every week together. The therapist modeled writing during the play, and the boy followed suit. The therapist modeled typing during play, and the boy followed suit. When his brain was too fast to get his ideas out through his hands, the therapist touched the dictation button on the tablet, and his brilliant ideas were transcribed by software, and the therapist helped him learn how to read back what he’d written and edit it.

The therapist and the boy moved freely around the room, as his brain leaped from idea to idea with the movement of his feet. The therapist never phrased corrections in terms of what he was doing wrong, but showed him how to make things work more smoothly when she saw him caring about something being better but not knowing how to do it.

The boy began showing up already full of ideas. The boy sometimes created parts of his ideas outside of therapy sessions. Thirty minutes a week was spilling into his own free time, his own free play, his own passion and imagination and delight.

Writing became a channel for meaning. Writing became a pathway for all the worlds that lived inside his head to exist concretely, on paper and in a digital world that he could re-access later and remember and delight in a second time, with the company of a supportive adult.

It had taken him longer to get there than it did for some other children, but now the world was opening up. There were so many new things to try.

***

I was the first therapist in 2019. I am the second therapist in 2024.

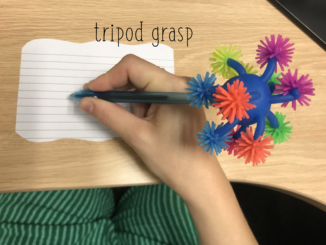

Prioritizing child-led play (for all ages, even big kids), and prioritizing relationship and rapport, and modeling writing as meaningful (without expectation or additional demands), and multiple modes of writing (handwriting, typing, dictation), and all the assistive technology that already exists in our world (dictation, predictive text, autocorrect, spell check), and prioritizing the sensory systems (movement, colorful writing tools, fidget tools), have changed my practice, and are changing my kids’ lives.

I don’t love them any more or less than I did in 2019. I have always loved my job and loved what I do. The whole change is in my brain, my framework for how I approach children. Whether I believe they need me to come down to them as an expert and a manager and pick and push and pull at them, or to trust them and follow their lead in discovering and expanding their own creative, clever, quirky, whole, amazing little selves.