It is extremely common and normal for children to reverse or invert letters when they are learning to write, or confuse those letters when they are learning to read.

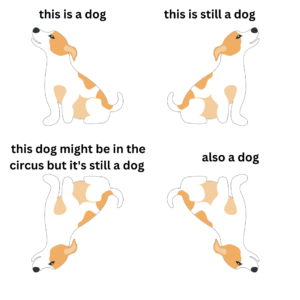

It makes perfect sense when you think about it. Take any other image or object in the world, and flip it horizontally, or look at it upside down, and it still stays constant — it’s the same object. A table. A pillow. A dog. The Eiffel Tower.

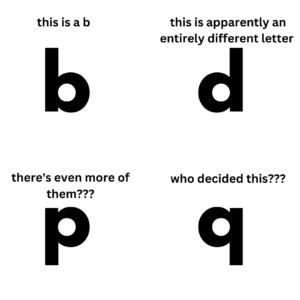

But letters and numbers, arbitrary symbols representing language that they are? Another layer of their arbitrary-ness is that some of them are meaningless if they’re flipped or inverted, and some of them are just a completely different letter if they’re flipped or inverted.

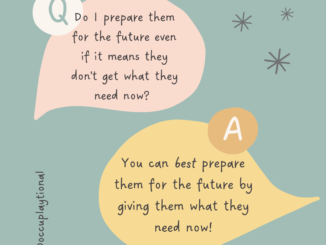

It takes time for children to learn this, just like it takes time for children to learn to differentiate left shoes and right shoes. They may get discouraged if they are constantly corrected on it, especially during the window where it is very normal for them to be reversing them (under the age of ~8).

For some children, especially (but not limited to) left-handed children, this will extend to writing entire words or sentences right-to-left. (It makes a lot of sense for lefties…that’s how you write and read it at the same time!) Again, the directionality of reading and writing in English is entirely arbitrary. Some languages and cultures read and write top-to-bottom, or right-to-left. Note that it being arbitrary doesn’t mean that it’s meaningless or that we should all write however we want…it just means that it’s a social construct, so there’s no inherent sense or logic to it that our kids will just intuitively understand, but rather, it has to be taught.

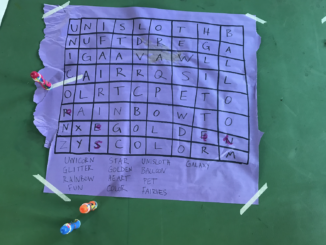

If a child is older than the window in which it’s normal to reverse or invert letters, or is struggling extremely with it even though they are still in that window (as opposed to reversing only a letter or two here and there), it may help to reduce the amount of correction. Rather than correct them on every single reversal, correct maybe 1 out of every 5. It can also help to give them a visual cue that they can reference themselves, so that the correction isn’t always coming “from” you, but rather “from” the visual cue (i.e., a laminated card with the ABCs printed on it, a poster on the wall, etc.)

Talking about, and playing games that involve, discriminating left from right, can sometimes help solidify the meaning in kids’ minds. Some examples of games that involve left/right: the Hokey Pokey, Simon Says, Left Center Right (a dice game), Left Turn Right Turn (a car game), etc. Or you can find ways to incorporate them into the play that your child is already playing, or the language you’re already using. An example of how to do this: your child asks you if you’ve seen their jacket and you tell them, “It’s on the left arm of the couch” — so their brain can scaffold the understanding of “left” by relying on “arm of the couch” if they don’t already know which one is “left”, and then can connect meaningfully to the new definition too.