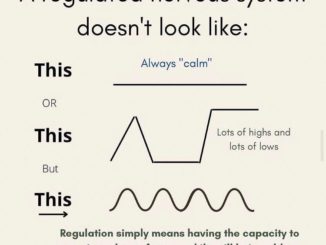

Most people — not all, but most — find rhythmic vestibular sensory input to be soothing.

Rhythmic: regular, repeated, predictable.

Vestibular: having to do with your inner ear, your sense of balance and movement. It is based on the motion, or lack of motion, of fluid inside of your inner ears. You can imagine human beings having a little tiny cup of water inside of each of their ears. If the activity would make water move, shake, or slosh around, then that’s the vestibular input that activity is causing. (It’s a little more complex than that, but that’s a simplification.)

Rhythmic input is usually rocking, spinning, swinging, moving in a predictable and repeated way. The imaginary little cup of water inside the ears would be moving predictably, the waves of water going back and forth in soothing, rhythmic waves.

Babies will often fall asleep on car rides, when being rocked, and may enjoy being bounced when carried. Their adults often instinctively bounce them and shush them when they fuss and feel unsettled. They are being settled by rhythmic vestibular input. (Also love and touch and emotional connection but I’m focusing on one thing for this post.)

Children often love to swing. Some children may spin around in circles, sometimes just standing on their own feet, sometimes on playground equipment, office chairs, or toys. On a long road trip with lots of highway driving, children may be lulled to sleep by the car. Or on a steady plane flight without turbulence. Rhythmic vestibular input can be very soothing.

Adults are often still soothed by rhythmic vestibular input. Think of the stereotype of a grandma sitting on the porch in a rocking chair! My partner and I stayed on a houseboat once and I slept like an absolute dream being gently rocked by the boat. Some adults still like to swing on larger swings or porch swings. Running can be a rhythmic vestibular activity for people who have practiced it for awhile and can get into a good pace and a state of “flow”. Even gently swaying my office chair back and forth while I work, or rocking back and forth on my feet while I talk, is rhythmic vestibular input.

Most people—not all, but most—find irregular vestibular input to be very alerting.

Irregular: sudden, jerky, unpredictable, movements.

If the imaginary little cup of water is getting sloshed wildly instead of smoothly, jerking around and splashing, that’s irregular vestibular input.

Sometimes “alerting” means that the person hates it. It might make them feel uncomfortable or even sick. Sometimes “alerting” means that the person loves it. It may make them feel delighted, amped up, silly, or energetic. Irregular vestibular input makes most people’s nervous system be on higher alert. That can feel good or feel bad.

Babies and toddlers might cry, scream, or resist being tipped backward for a diaper change. It’s an irregular movement (not predictable, not rhythmic) that is alerting their brain. It makes them feel unstable and insecure and like they are falling. Their system is alerted, and with that flood of alerted energy, they resist.

Babies and toddlers might laugh and scream and delight in playing games that involve tipping back, or bouncing on your knee and then suddenly “falling” (safe in the arms of their parents); the sudden, irregular vestibular input alerts their system and floods it with delight and excitement.

Babies and toddlers might cry disproportionately to the amount of actual pain or injury when they’re suddenly knocked over or trip on something. They might be physically totally fine in every way, but their system was overwhelmed with a jolt of alerting sensations and the release of it is crying as they process the sudden, unexpected movement of falling over.

Children might get off the bus for school in the morning already disgruntled and overstimulated. The jostling and bumping of a much larger, longer, bouncier vehicle has set their system on high alert, leaving their senses feeling raw and irritable.

Children might seek wild forms of movement in play like somersaulting, cartwheeling, rolling around, spinning and stopping and spinning. It can seem to “amp them up” instead of “calm them down” or “get their wiggles out”; when they began to play, they might have been emotionally ready for the rough-and-tumble movement play but not actually physically alerted yet, but the sudden quick starts and stops of roughhousing movement actually alert their system, making them seem like they’re getting even wilder.

Teens and adults might enjoy (or loathe) rollercoasters, spinning rides, going upside down, etc. It might make their bodies feel terrible (🙋🏽) because they feel alert and under threat, ready to defend from the threat. Or it might make them feel great, exhilarated, delighted.

Vestibular input is extremely potent and powerful. Sometimes people love and crave the alerting sensation but it doesn’t actually seem to make them feel better to get endless amounts of it. (Just like other things people can love and crave.) This happens in my job sometimes, where a kid, for example, adores spinning but makes themselves sick, so high energy they become dangerous to themself, or tearfully dysregulated by spinning so much.

Sometimes pairing vestibular input with proprioceptive input — deep body pressure input — can help; for example, spinning for a short while, and then sitting with a weighted blanket or getting a long, squeezy hug while the imaginary “cup of water” stills itself back down. Or swinging for awhile, and then doing some big jumps on the trampoline, rolling up as a burrito in a blanket or burrowing into a pile of stuffed animals.