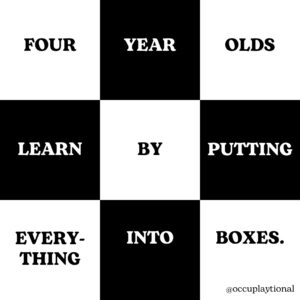

Note: I don’t mean literal boxes. Although they might do that too. 😉

Four-year-olds (and five- and six- and even seven-year-olds, and maybe three-year-olds, and yes maybe even older depending on your unique child — but here I’m talking about averages and norms) are very black-and-white. They do not understand intricacies and nuances.

They are learning to make categories, a very complicated thing that humans are able to do and hold in their head. They are learning that when you hold up an apple, it also fits into the category of “fruit”, which also fits into the category of “food”, but does not fit into the category of “clothing”. They know so many hundreds or thousands of words by now! All of those words have to fit into larger boxes of some kind, otherwise the process for selecting those words from their memory banks would be so overwhelming and impossible by now.

Most adults don’t have a problem with anything I’ve described so far. It makes perfect sense that children are learning to sort things into categories.

Where adults start having a problem with it is when this categorization starts to overlap around the edges of “things that seem like they have to do with morality” or “things that seem like they have to do with complex societal factors”.

Like…X goes in the category of Good Guy, but Y goes in the category of Bad Guy.

(And then the adult’s brain wants to explain, “But Y isn’t really a bad guy, and no people are Bad People, there’s just people who make bad choices…”)

Or…X goes in the category of Things For Girls, and Y goes in the category of Things For Boys.

(And then the adult’s brain wants to explain, “But things aren’t just for girls or for boys, things can be for both girls and boys, and the gender spectrum is more complicated than just a simplistic and childish binary anyway…”)

Or…X goes in the category of Fair, and Y goes in the category of Not Fair.

(And the adult’s brain wants to explain, “But Y was perfectly right and just for so-and-so, for complicated factors that you can’t understand because you’re 4.”)

And that’s really the thing: They can’t understand, because they’re 4.

It’s developmentally normal for a four (or five or six or three) year old to understand things through a simplistic and childish binary, because they are a child and the world is simple.

As with almost everything I ever post about developmental norms: That does not mean that you should never introduce nuance to your child. Or that you can’t teach them that colors are for everyone, not just pink for girls and blue for boys. (I personally have conversations with children all the time about gender norms because I look more or less androgynous depending on what I wear and what society thinks about it!) You can totally talk about these things with your children. You can totally casually reply from the adult perspective that you hold.

(But if you do it all the time, you risk them feeling like you never hear what they’re saying.)

I hear from parents a lot who are super concerned about why their child has picked up good guy/bad guy language. Or “that’s for girls” or “girls can’t do that” language. “They didn’t learn this at home! That’s not what we (read: me, the parent) believe!” I wonder how much of parents’ reaction is feeling anxious about their child expressing a belief that would sound immature or even offensive coming out of an adult’s mouth. But it’s supposed to be immature. They’re immature. They’re not mature. They’re 4.

They will continue to develop nuance as they grow, as their brain physically matures and makes space for nuance. As you continue to model nuance and your beliefs in it. They will learn much more from your modelling than they do from adult lectures! They will learn much more from exposure to a diverse range of ideas in their media and in your friendships and in their available playmates.

And if you want to push back, just make sure you’re hearing them first. Spend the first half of the conversation in “Oh?” and “Hmmm…” and “What makes you think that?” and maybe by casually pointing out the examples of nuance that they already know but might not have assimilated into their categorization system yet.

(i.e., “Oh, somebody told you that only boys can have short hair? What do you think about that? We do know lots of boys with short hair, you’re right…Your brother has short hair…Dad has short hair. Hmm. I can think of a girl with short hair, though. What about Grandma? I wonder if we know any more… I wonder what makes someone a boy or a girl… Is it really their hair? … Huh… interesting.” with lots of pauses for them to interject their own thoughts and reflection and not rushing toward your ability to explain your adult perspectives)

There’s no need for alarm. This is 4. This is what 4 does. And the more that you model not being an adult who can only put things in boxes, the more that they’ll learn to grow up to be like you.