Autism and ADHD. Autism and OCD. Autism and anxiety. Autism and Tourette’s. Autism and trauma.

Autism (as a diagnosis) very commonly accompanies other diagnoses as well, which typically fall into different categories: some of them are mental health-related, some of them are physical (especially gut/digestion, vision/hearing, joint, or coordination related), and some of them are developmental, like intellectual or language delays.

The overlap between autism and other diagnoses (a medical word for this is “comorbidity” – when you have one diagnosis and also another at the same time; but many Autistic people prefer the word “co-occurring” rather than “comorbid”, because the latter implies autism as a diagnosis rather than as a neurotype) can complicate the diagnostic criteria for both autism and the other diagnosis.

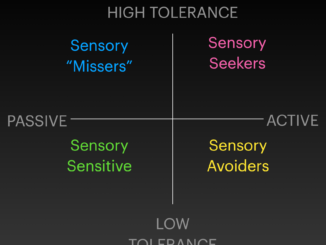

Someone with autism and ADHD may have a hard time sorting out which of their symptoms has to do with which thing, and some of their traits may seem opposite of “classical” ADHD or autism because they’re actually stemming from an interplay between the two. Someone with sensory processing difficulties (like, for example, diminished interoception) might have a hard time interpreting the sensations from their gut/digestion in order to seek treatment for difficulties on that front.

Sleep disorders co-occur with autism so commonly that they could probably be their own post as well. For many families with autistic children, the lack of quality sleep all around – on all parts of the family members – can be the hardest thing to cope with.

When it comes to kids with severe disorders like blindness, deafness, cerebral palsy, severe epilepsy, etc, it can be very hard to get autism diagnosed in the first place because their symptoms look more like they’re stemming from a physical disorder and not from a neurodivergence.

The image attached to this post is a story/joke from Tumblr that reads thus:

“Imagine working in tech support and someone calls in like, ‘hello, I can’t use my keyboard,’ and after you’ve double-checked that it’s turned on, the computer is turned on, the keyboard is properly installed, you have no idea what could possibly be wrong, and you ask.

‘Well, every time I try to push down one key, multiple keys go down. Like, half the keys on that side.’

‘Is there… Any foreign objects on them? Dirt?’

‘Of course not, I’ve been very careful with taking good care of it.’

And you go around trying to figure out what the heck could be wrong, until you ask whether the customer might be trying to type with mittens on their hands.

‘Oh, I don’t have hands at all. I’ve got hooves.’

‘Sir, are you a horse?’

The customer groans. ‘Oh come on, this is a horse thing, too? Why does everything come down to me being a horse?’

You try to be professional at this outburst. ‘Well, sir, I’m afraid I don’t think there is anything wrong with the keyboard. You have a hard time with typing because you are a horse.’

‘This always f— happens. Well, thank you for your time.’

…And that’s roughly what it’s like when I’m asking advice on anything unrelated to mental illness.”

I share this as a good analogy for a few things:

1. This is what the autistic experience can sometimes be like, if the medical providers they’re seeking help from are lazy, uninformed, ignorant, or not willing to give them the benefit of the doubt on trying to seek out help for things that they don’t feel are related to their autism. It can be massively frustrating if someone already has a diagnosis of autism, and they feel like there’s a good reason to delve deeper into a specific issue that they’re dealing with, and the medical provider is just like “welp that’s a part of autism too.” Granted, in the story, a horse *can’t* type with a human keyboard, so that leads me to point number two…

2. Hey hey, we’re back to my most favorite talking point for almost everything I do, which is: what if we change the environment? Does it change or mitigate the symptoms? What if we get a big horse-sized keyboard? Does the problem go away? Now, it’s not always 100% going to do that, which takes me to my next point…

3. Let’s imagine that the analogy is actually for something different. We’ll say that instead of trying to type with a keyboard, the horse is trying to do something that is more necessary for everyday life, but hooves just can’t do…like put on clothes, or brush teeth/brush hair, or feed themselves with a utensil. (Although my “analogy brain” is protesting “but why do you need to use utensils at all? What if we change the environment and the expectations?” 😉 ) But let’s say it’s something that the horse WANTS and NEEDS to be able to do and they just cannot. Due to autism or due to a co-occurring condition, they are not capable of doing this thing, and yet the environment is not capable of changing to accommodate them.

Someone pointed out on one of my posts the other day that *this* is where autism can fall under disability. Literally, from the root of the word “disability”: this is an inability to do ____. Personally, the only dis-abling conditions that I think are worth tackling at their root are ones that the person themself cares about, not one that society or someone else is trying to enforce on them – in those instances, I would instead wield a diagnosis to try to work on getting accommodations, changing the environment, or changing the expectations.

Some further reading on this if you’d like:

Conditions That Accompany Autism

Comorbidity Clusters in ASD