I can understand why some fidgets get labeled as “toys” — or worse, “distractions” — and taken away from kids who need them. It’s because they’re sold in bulk and trendy and seem like fun to all kids, not just kids who need a fidget to focus.

Fidgets — sensory tools for tactile (touch) or movement needs — are the obvious thing that comes to mind when talking about “sensory tools”. But there are lots of other things that could fit this description, too. You might even use some yourself without thinking about it: maybe you twirl your hair around a finger, chew gum (or your lips or fingernails!), or begin doodling on the margins of a paper as soon as you have to sit still for a meeting or class.

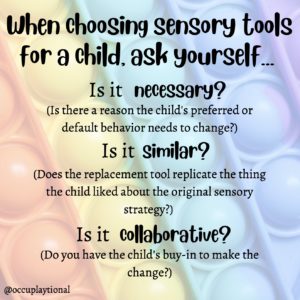

There are lots of in-body sensory processing functions that happen without us even thinking about them. Sitting with a foot tucked under the body (rather than at sharp ninety-degree angles) provides a little extra proprioceptive input to the joints of the body. Chewing lips or fingernails provides tactile (touch) and oral input. So when is an actual, external, sensory tool needed? These are the questions to ask yourself in order to decide if a sensory-processing-related behavior needs to be changed, and how to choose the tool to change it.

Is it necessary?

I once had a referral for OT services. The teacher was concerned because a 5-year-old was “showing sensory-seeking behavior”. When I drilled to figure out what they meant by that, it turns out that he was fiddling with his shoelaces. I asked if the shoes were coming untied and if they had tried double-knotting them. They had, and the shoes were not coming untied. I struggled to think of another reason why this would be a problem and finally just asked, “So what is the problem?” They didn’t have an answer. It wasn’t a problem, they just saw him fiddling all the time and jumped straight to thinking that sensory-seeking itself was a problem!

So, could I have found that child a fidget to replace his shoelaces? Yeah, probably. Would that have been any better? To give him something that other kids might think was a toy, could take away from him (or he could offer to them), thereby possibly causing classroom distraction? And something that he might lose or misplace or not have with him when needed (as opposed to his shoes on his body)? Nah. Doesn’t seem worth it to me. It wasn’t necessary: no tool choice needed.

But I’ve also had children referred to me because their coping strategy of choice is to, say, pick at their skin until it bleeds, or chew holes in their shirt until it comes apart. So in those cases, we can say yes, it’s necessary, and that takes us to step number two…

Is it similar?

A lot of well-meaning parents and teachers will try to educate themselves about sensory processing difficulties. They’ll read some blogs or some Facebook posts, they’ll see something, and jump on it — usually whatever is popular or a fad at the time. Child is chewing holes in their shirt? Well, I’ve heard of this new thing called “Chewelry” — chewable, silicon jewelry — and that sounds great!

For some kids, that kind of a swap works just fine. For others, it super doesn’t. Hard, rubbery silicon does not feel the same against the lips and teeth and tongue as soft, cottony shirt. And if it’s not similar enough to actually meet the need that someone is subconsciously seeking out, then they’re just going to ignore the replacement solution and stick to their original coping strategy.

I had a girl on my caseload years ago, when I worked in a setting for children with very high support needs. She was routinely scratching at her cheeks until they bled. Her team (educators, parents, etc) tried all kinds of serious bandages on her face, making sure her fingernails were always clipped, giving her things to scratch against like scratch-n-sniff stickers, etc. A lot of the assumption was that the “need” she was trying to meet was the need to scratch, i.e., a need located “in” the fingers (as a sort of way to think of it, not a literal statement). With careful supervision, we tried something new: we gave her a blanket/lovey to hug and rub against her face that had a section of poky velcro, the “hook” side of hook-and-loop. It almost completely eradicated the behavior. Again, there was very careful supervision because she could theoretically have scratched herself enough with the velcro to continue to cause damage, but she rarely did, and we made sure it was a very small section of velcro so that she could seek out that very intense sensation of scratching against cheek without doing as much damage to her actual skin. This shifted the idea that the need was “in” the fingers to “in” the cheek — she wasn’t seeking *to scratch* so much as seeking *to be scratched*. (Again, that’s not a literal statement, but a way of visualizing what our replacement tool was going for.)

So assuming a replacement is necessary, and we’ve found an option or several options that are similar. The last question is, is it collaborative?

Getting the child’s participation and buy-in into their own care and life is obviously a powerful tool at all times. Who doesn’t want autonomy over their own life?

Some people hear “collaborative” and think “we just need to ask the child what would work for them.” This might help sometimes. Sometimes, a child doesn’t know what would work for them, or can’t verbalize it, and that’s okay too. We are the professionals (or, at very least, we are the adults with access to professionals!)

Foisting a new replacement tool on a child with no warning and expecting them to use it appropriately, or expecting them to take to it or enjoy it, doesn’t always work out that way. Even worse — sometimes I’ve seen a child be given something and expected to treat it with gratitude like it’s a gift! And then if they struggle to use the new tool, or don’t like it as much as the old one, the adult gets angry or grumpy about it.

Think of it like a tool, not a toy. It is sometimes hard to learn to use new tools you’ve never used before. It is hard to break old coping strategies that have worked reliably (yet still need changed for some reason, as we determined in point #1).

Imagine the way that you like to fall asleep. If someone told you that they were going to change all of your preferred sleeping methods — if you sleep on your side it’s going to change to your back, or stomach, or vice versa; you had to use a new, differently-shaped pillow of different thickness; you were going to have a nightlight on or off, and white noise on or off (depending on how you currently sleep); your sheets and blanket were going to be replaced with wholly new ones and your mattress with a different kind…all of those changes might technically be “good”, or at least equally fine, but they also might still annoy or frustrate you as you tried to get used to the new normal. You might find yourself rolling to your side, and needing a (gentle and patient!) cue to sleep the “new way”.

It’s the same with our children who need a new sensory coping tool for some reason. And if you get collaboration, or enjoyment, or enthusiasm from the process, it makes it that much easier — and puts them that much more in control of what their body needs throughout their life.